Scientists have managed to squeeze a working computer into a robot so tiny it’s comparable to a grain of salt—and it can move, sense, and “decide” on its own for months.

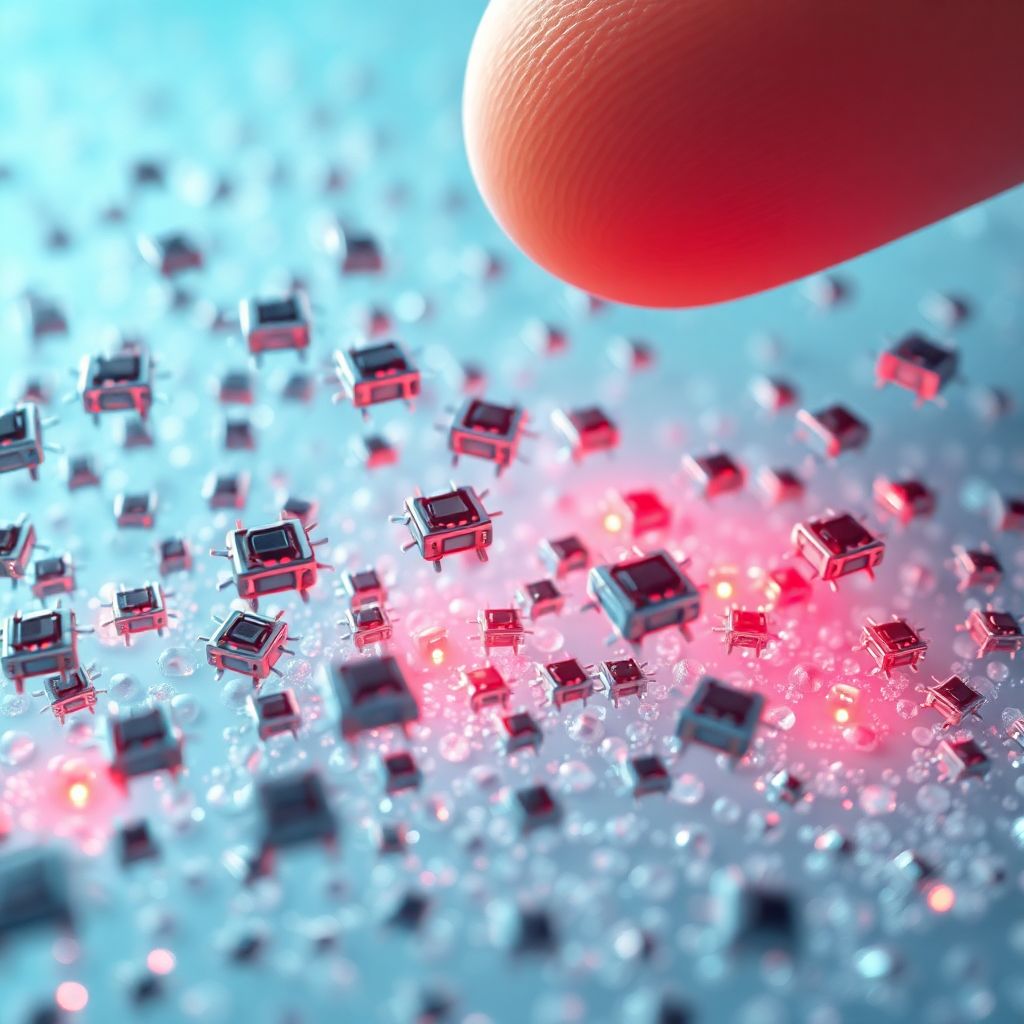

A research collaboration between the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan has produced microscopic robots measuring roughly 200 by 300 by 50 micrometers. That’s about the size of a speck of dust or a salt crystal, yet each of these minuscule machines houses an onboard computer, sensors, and a propulsion system that allows it to swim through liquid and react to its environment.

Despite their size, these robots are not remote-controlled gadgets. They are designed as fully autonomous systems. There are no wires tethering them to external power supplies, no magnetic fields steering them from the outside, and no operator with a joystick guiding their movement. Instead, each robot carries its own logic circuitry and control system, enabling it to process information and take action independently.

The robots can detect temperature changes in the fluid around them and adjust their behavior based on those readings. That means they don’t just move randomly; they can respond to what they “feel” in their surroundings, using basic decision-making rules embedded in their tiny onboard computers. In engineering terms, it’s a primitive form of thinking, but at a scale that was previously out of reach.

Equally striking is their endurance. Once deployed, these robots can keep operating in liquid environments for months at a time. Their extremely low power requirements and efficient design let them carry out long-term tasks without constant external input or energy replenishment, a crucial feature if they’re ever to be used inside the human body or in hard-to-reach environments.

Cost is another major achievement. Each robot reportedly costs about one cent to manufacture. That kind of price point opens the door to producing huge swarms—thousands or even millions of units—for applications where redundancy, coverage, and sheer numbers matter more than the capabilities of any single robot.

The core breakthrough lies in miniaturizing what we normally think of as a computer into something smaller than most dust particles. The team has effectively packaged computation, sensing, and motion into a volume that previously could only accommodate passive electronics or simple particles. This level of integration at microscopic scales pushes the frontier of what counts as a “robot.”

Traditional microrobots often rely on external fields—magnetic, electric, or acoustic—to move or perform tasks. In those designs, the robot itself is more like a passive object being pushed around by outside forces. By contrast, these new salt-grain-sized robots embody the key traits of autonomy: they sense, process, and act locally. That shift from externally driven particles to genuine, self-governing machines is what makes this work so significant.

Making robots “10,000 times smaller,” as the research team notes, isn’t just shrinking a familiar device. At these scales, physics behaves differently. Viscous forces dominate over inertia, surfaces matter much more than volumes, and simple tasks like moving in a straight line become complex challenges. Designing motors, actuators, and control systems that function reliably under these conditions is a major engineering and scientific accomplishment.

The potential applications are vast, even if many are still speculative. In medicine, such robots could eventually be deployed inside the body to monitor conditions, deliver drugs to precise locations, or help map tiny structures like capillaries and microscopic tumors. Their ability to sense temperature, for instance, hints at future capabilities to detect inflammation or abnormal tissue states with far greater resolution than current tools.

Beyond health care, autonomous micro-robots could be used to explore complex, constrained environments where larger devices simply cannot go. They might travel through microfluidic channels in lab-on-a-chip systems, monitor chemical processes inside industrial equipment, or sample contaminants in soil and water at a microscopic level. Because each robot is cheap and small, researchers could deploy them in massive numbers to build highly detailed maps of physical or chemical conditions.

Another intriguing direction is swarm behavior. When robots are this inexpensive and compact, the focus shifts from the power of an individual unit to the capabilities of a collective. Thousands of salt-sized robots working together could average out noisy measurements, form dynamic patterns, or coordinate to explore an environment more effectively than a single large robot ever could. Programming and controlling such swarms, however, presents a new set of challenges in distributed computing and communication.

Power and communication remain central technical hurdles. At this size, you cannot simply attach a battery or a traditional wireless antenna. Researchers must rely on extremely minimalist electronics, novel methods to harvest energy from their surroundings, and clever schemes for signaling or coordination that do not require bulky components. The fact that these robots can already operate for months suggests that highly efficient power strategies are either built in or being developed in parallel.

Ethical and safety questions will inevitably grow alongside the technology. Robots that are too small to see raise concerns about surveillance, privacy, and unintended presence in environments where people have no way of detecting them. In medicine, strict controls will be required to ensure that microscopic devices can be tracked, deactivated, or removed, and that they do not accumulate or behave unpredictably in the body over long periods.

Regulation and standards will also need to evolve. As micro-robots move from laboratory prototypes to real-world tools, clear guidelines will be needed for their use in clinical settings, industrial operations, and environmental deployments. That includes protocols for testing biocompatibility, preventing contamination, and guaranteeing that these systems do not persist in ecosystems in harmful ways.

On the scientific side, these salt-grain robots provide a new testbed for studying fundamental questions in robotics and control. How simple can a robot be and still meaningfully “decide”? What’s the minimum amount of computation needed to perform navigation, sensing, or basic cooperation at microscopic scales? By pushing hardware to the limit, researchers can explore the boundary between passive matter and active, adaptive machines.

The work also hints at future convergence between microelectronics, synthetic biology, and materials science. As robots become smaller and more integrated with their surroundings, the lines blur between a traditional machine and an engineered, responsive material. It’s not hard to imagine future systems where micro-robots are embedded into fabrics, coatings, or even living tissues, turning ordinary surfaces into active, sensing, and self-adjusting structures.

Despite the excitement, it’s important to recognize that these salt-sized robots are still at an early stage. Their decision-making is basic, their sensing limited, and their mobility constrained by the physics of their environment. Scaling from laboratory demonstrations to robust, field-ready tools will likely take years of engineering, testing, and iteration.

Still, the trajectory is clear. Compressing computation, sensing, and movement into a package smaller than a grain of salt fundamentally changes what is possible in robotics. As researchers refine the design, expand the range of sensors, and develop more sophisticated control algorithms, these microscopic machines could become powerful instruments for medicine, science, and industry—quietly swimming, sensing, and thinking in places too small for us to ever see directly.