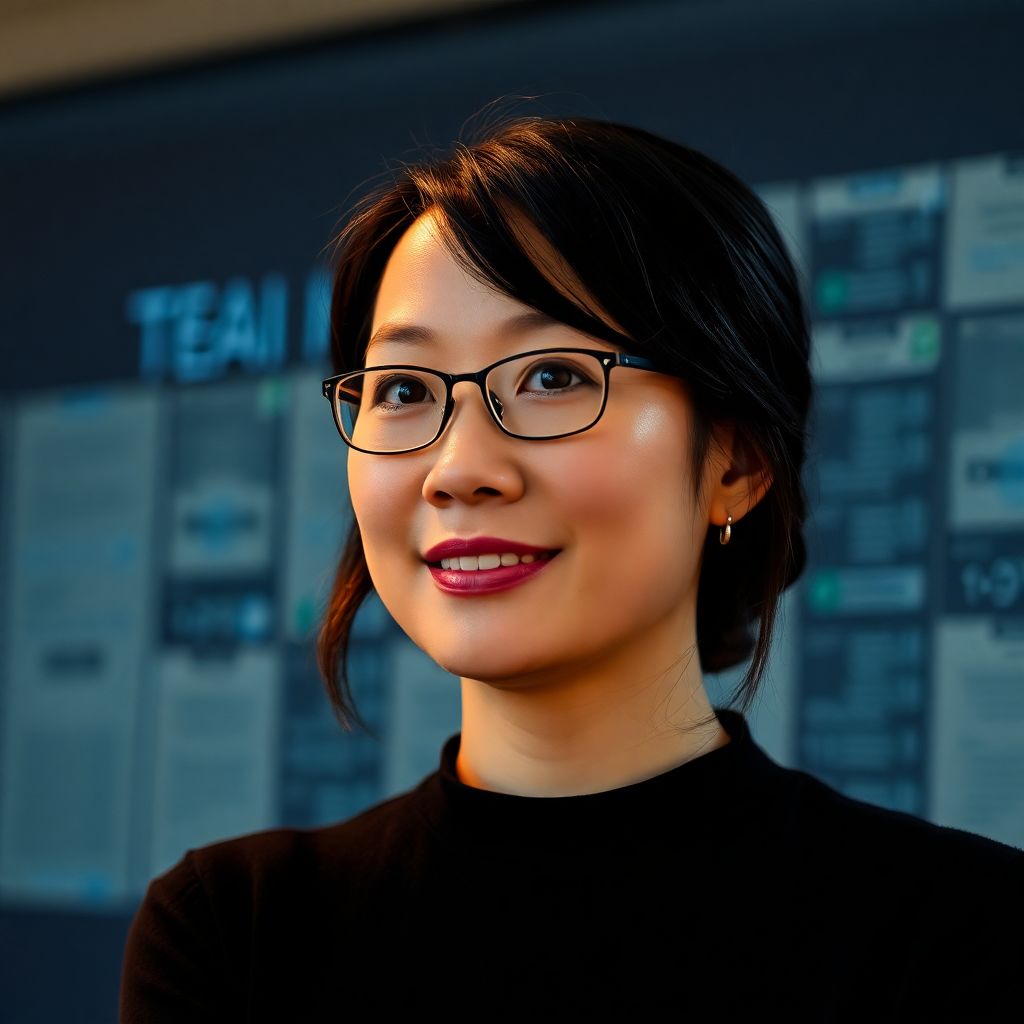

Artificial intelligence has made tremendous strides in recent years, particularly through language models capable of generating human-like text. However, leading researchers now argue that this progress may be reaching a ceiling. According to Fei-Fei Li, a prominent Stanford computer scientist and pioneer in computer vision, the next leap in AI will depend on developing systems that can understand and interact with the physical world—something current models still struggle to achieve.

Li emphasizes that the major roadblock facing AI today is its inability to fully comprehend the spatial and physical dynamics that govern our reality. While language models like ChatGPT and others have shown impressive capabilities in processing and generating text, they remain fundamentally limited by their lack of understanding of the real-world environments humans navigate daily.

This limitation has given rise to the concept of “world models”—a new paradigm in AI research aimed at creating systems that can simulate, predict, and reason about physical environments. Unlike traditional generative models that operate purely in the realm of language or static images, world models are designed to incorporate sensory input, spatial awareness, and temporal continuity. These models aim to mimic the way humans build mental representations of their surroundings, enabling more robust decision-making, planning, and interaction with the environment.

World models are not just theoretical constructs—they are beginning to take form in experimental systems that combine computer vision, motor control, and reinforcement learning. By training AI to understand cause-and-effect relationships in space and time, researchers hope to create machines that can learn more like children do: through exploration, manipulation, and observation of their environment.

The current generation of AI, while impressive, often lacks what Li refers to as “embodied intelligence”—the capability to understand the world not only through language but by physically engaging with it. This is why even the most advanced chatbots can describe how to stack blocks or navigate a room, but cannot perform these tasks themselves or understand the nuances involved in real-world execution.

This gap is especially apparent in robotics. Despite advancements in machine learning, robots today still struggle with seemingly simple tasks like folding laundry or walking on uneven terrain—tasks a human toddler can accomplish with ease. The reason lies in the lack of a comprehensive world model that allows machines to predict outcomes, adjust to changes, and learn from physical interaction.

To bridge this divide, researchers are increasingly turning to multimodal AI—systems that combine text, vision, audio, and physical sensor inputs to form a unified understanding of the world. These systems are being trained not just on datasets of text or images, but on simulations and real-world interactions that teach them about physics, motion, and spatial relationships.

The implications of successfully developing world models are significant. In fields such as autonomous driving, household robotics, and industrial automation, AI that understands the physical world could dramatically increase safety, efficiency, and adaptability. Such systems would be able to learn new tasks without massive retraining, adapt to unfamiliar environments, and interact with humans in more intuitive ways.

Moreover, world models could revolutionize digital agents and virtual assistants. Instead of merely responding with pre-trained responses, AI could simulate potential actions and outcomes in real time, offering far more context-aware and practical assistance. For instance, a healthcare assistant could anticipate patient needs based on movement patterns, or a construction robot could navigate complex terrain while adjusting to unexpected variables.

Another major benefit of world models lies in their potential to enhance generalization. Current models often fail when presented with situations not represented in their training data. World models, by contrast, could enable AI to infer solutions to novel problems by leveraging an internal understanding of how the world works, much like humans do.

Of course, building such systems poses its own challenges. Training AI to understand physical reality requires vast computational resources, carefully curated multimodal data, and advanced simulation environments. Furthermore, aligning such models with human values and ensuring safety in unpredictable scenarios adds another layer of complexity.

Despite these hurdles, momentum is growing. Major tech companies and research labs have begun investing heavily in world modeling, recognizing that the future of intelligent machines depends on their capacity to reason about more than just words. The transition from language-dominant AI to spatially aware, physically capable systems marks a fundamental shift in the field—one that could redefine the boundaries of what machines can achieve.

In summary, the next chapter in AI evolution hinges not on refining language models, but on imbuing machines with the ability to understand and navigate the real world. World models represent a critical step toward this goal, promising AI systems that are not only articulate but also perceptive, adaptive, and deeply grounded in physical reality. This shift could unlock new levels of autonomy and intelligence, enabling machines to engage with the world in ways previously thought to be the exclusive domain of humans.

As this new frontier unfolds, interdisciplinary collaboration will be key. Advances in neuroscience, cognitive science, robotics, and computer vision must converge to build AI systems that truly grasp the nature of our world. Only then can we move beyond the limitations of text and toward a future where artificial intelligence is not just intelligent, but embodied and aware.