FCC regulators have begun scrutinizing an ambitious SpaceX proposal that could push artificial intelligence infrastructure far beyond the bounds of Earth—literally into orbit. The company, led by Elon Musk, wants to build a massive network of space-based data centers, using a new non‑geostationary satellite system to run energy‑hungry AI workloads above the planet’s atmosphere.

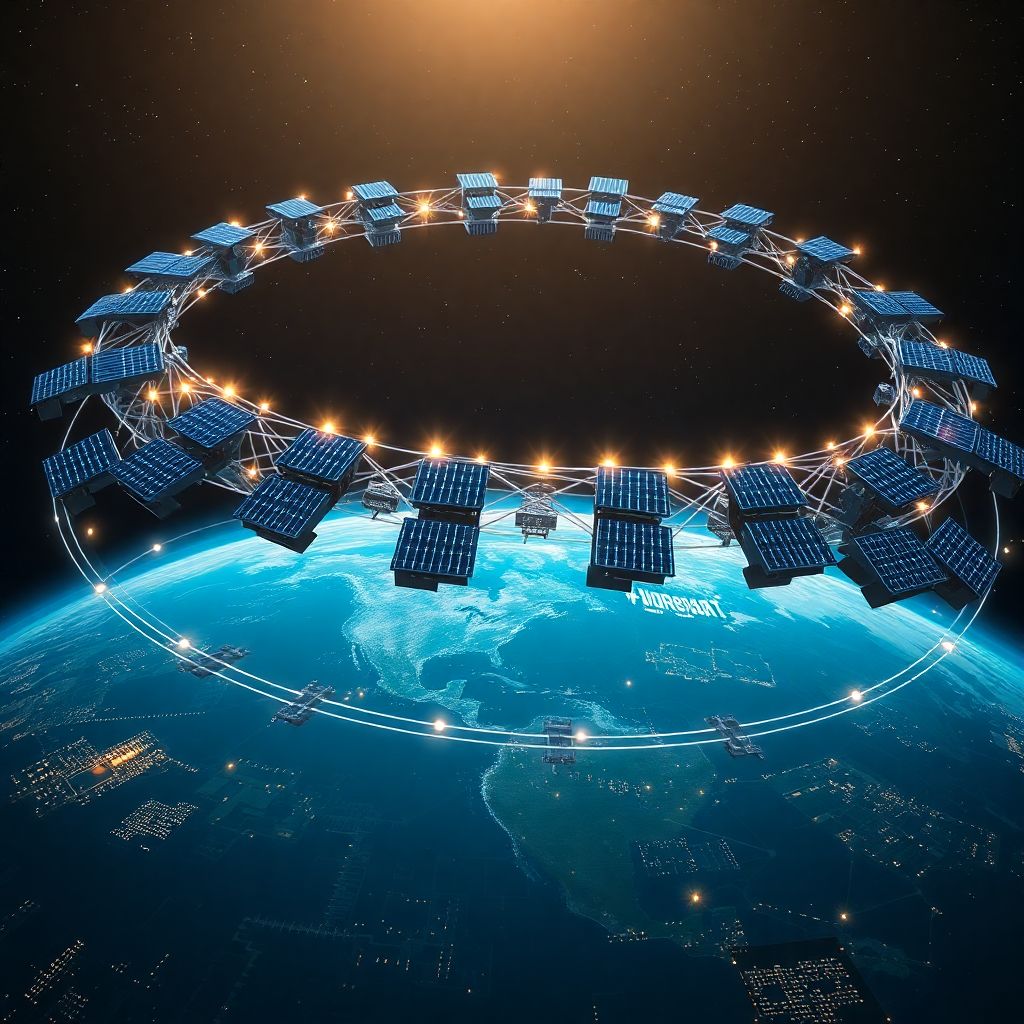

According to the application now under review, SpaceX envisions deploying up to one million satellites configured more like data center racks than traditional communications hardware. These “orbital data centers” would be dedicated to training and running AI models from Musk’s AI venture xAI, including its flagship chatbot Grok, by shifting the most power‑intensive computation into space.

The Federal Communications Commission has formally opened a public comment period on the proposal. In its notice, the agency highlighted that the planned constellation would rely on “high‑bandwidth optical inter‑satellite links” to shuttle data among spacecraft, while also performing standard telemetry, tracking, and command (TT&C) operations needed to manage such a fleet. The FCC is now seeking input on both the technical aspects of the system and SpaceX’s requests for regulatory waivers required to make it viable.

This review comes on the heels of the commission’s earlier approval of SpaceX’s so‑called Gen2 Starlink expansion—a second generation of broadband satellites designed to increase capacity and coverage. The orbital AI infrastructure plan builds on that foundation but goes much further, repurposing the core architecture of satellite internet into something akin to a distributed supercomputer wrapped around the planet.

In Musk’s vision, the night sky effectively becomes a vast, solar‑powered computational layer. Solar arrays on the satellites would harvest energy, while radiative cooling in the vacuum of space could help manage thermal loads that constrain terrestrial data centers. With enough nodes in orbit, SpaceX argues, the system could rival or exceed ground‑based GPU clusters in raw scale, while being less constrained by land, power grids, and cooling infrastructure.

Technically, the concept leans heavily on laser‑based optical links, the same type already used in advanced Starlink units to pass traffic directly between satellites instead of routing everything through ground stations. For AI, those links become the backbone of a high‑speed, low‑latency network fabric connecting countless compute nodes. That fabric is critical if large models are sharded across many satellites or if training data and gradients must be synchronized at massive scale.

From a regulatory perspective, however, the idea raises complex questions. The FCC must evaluate not only spectrum use and interference with other satellite operators, but also orbital congestion, collision risk, and long‑term space debris. A constellation that could eventually include up to a million units exponentially increases the stakes of any failure in de‑orbit plans or traffic management protocols.

Critics of megaconstellations have already voiced concerns about how large satellite swarms affect astronomy, night‑sky visibility, and the safety of other spacecraft. Layering heavy AI compute hardware onto those platforms adds another dimension: these are not lightweight communications satellites, but effectively mobile servers that could demand more power, generate more heat, and require more robust station‑keeping than standard designs.

Supporters of the project, on the other hand, see it as a potential breakthrough in scaling AI safely and sustainably. Ground‑based data centers are under growing pressure as AI model sizes balloon and energy consumption surges. Building new facilities requires vast quantities of land, water for cooling, and grid upgrades. By contrast, orbit offers uninterrupted sunlight in many configurations, natural radiative cooling to deep space, and freedom from terrestrial zoning or NIMBY opposition.

Security is another strategic argument SpaceX is likely to emphasize. Hosting critical AI infrastructure off‑planet could make it more resilient to physical attacks, regional power failures, or natural disasters. Combined with end‑to‑end encryption over optical links, an orbital AI network might be pitched as a hardened platform for both commercial and government use, including national security applications.

Still, the project is not purely technical or environmental; it touches directly on the geopolitics of AI and space. If SpaceX and xAI succeed in creating a globe‑spanning AI compute layer controlled by a single corporate ecosystem, questions will arise around governance, access, and competition. Who gets priority on orbital GPUs? How are resources allocated between consumer applications, enterprise workloads, and strategic state uses? Regulators will be under pressure to ensure the system does not entrench an unassailable monopoly over orbital compute.

Another unresolved issue is data jurisdiction and privacy. AI models trained in orbit will still rely heavily on data sourced from Earth, which may be subject to a patchwork of national and regional regulations. Moving the compute layer into space doesn’t magically exempt it from data protection rules, export controls, or content restrictions. Legislators and agencies will need to clarify which legal frameworks apply when sensitive data is transmitted to and processed by satellites circling above multiple countries simultaneously.

The economics of the plan are equally complex. Launching, operating, and eventually de‑orbiting up to a million satellites is staggeringly expensive, even with reusable rockets and falling launch costs. SpaceX is betting that the market demand for AI compute will be strong enough—and constrained enough on Earth—to justify the investment. If the price of orbital compute can compete with or undercut terrestrial data centers, especially during peak demand windows, major AI labs and enterprises might see it as an attractive overflow or primary platform.

There are also technical unknowns. Training frontier‑scale AI models requires ultra‑reliable, high‑throughput access to huge datasets and frequent model updates. Although inter‑satellite optical links can be extremely fast, the system must still move data up and down between space and ground. Latency, bandwidth caps, and the cost of ground infrastructure could all limit the efficiency of orbital training compared to conventional hyperscale facilities.

For astronomers and space environment advocates, the FCC review will be a critical moment to push for stricter guardrails. They may argue for tighter limits on the number of satellites, mandatory de‑orbit timelines, more stringent brightness controls, and robust collision‑avoidance capabilities that go beyond current industry norms. SpaceX, for its part, will need to demonstrate that its designs can coexist with other space users while delivering on the promised AI benefits.

From the AI community’s standpoint, the proposal underscores how aggressively infrastructure is becoming a strategic differentiator. Access to GPUs and other accelerators has emerged as a bottleneck for both startups and established tech giants. By creating a vertically integrated orbital layer—from rockets to satellites to AI models—Musk is trying to secure a long‑term advantage for xAI and its products like Grok, independent of third‑party cloud providers.

The FCC’s process—collecting comments, evaluating technical filings, considering waivers, and potentially imposing conditions—will likely unfold over months rather than weeks. During that time, stakeholders across telecom, space, AI, and environmental policy will seek to shape the outcome. The agency will have to balance innovation and national competitiveness against concerns about orbital sustainability and market concentration.

In the broader context, SpaceX’s orbital AI data center plan signals where the frontier of infrastructure is heading. As computing demands continue to explode, companies are no longer thinking only in terms of new chips or bigger buildings, but of new layers of physical reality to exploit—under the sea, inside specialized nuclear‑powered campuses, and now, in orbit. Whether or not this particular proposal is approved as‑is, it marks the beginning of a serious conversation about off‑planet AI compute and the rules that will govern it.

For now, the project remains an audacious blueprint: a planet‑encircling lattice of AI‑optimized satellites, powered by the sun and linked by beams of light, training and serving models far above the clouds. The FCC review is the first major gate it must pass. What regulators decide will help determine whether Musk’s vision of a “solar‑powered brain in the sky” becomes a cornerstone of tomorrow’s AI ecosystem—or stays, at least for a while longer, in the realm of speculation.